2015

Kaaka Muttai

Drama

8.0

User Score

63 Votes

Status

Released

Language

ta

Budget

$0

Production

Wunderbar Films, Grass Root Film Company, Fox Star Studios, Fox International Productions India

Overview

Two slum kids yearn to taste a pizza after being enticed by the pizza shop that has opened near their locality. What happens when they manage to find the money to buy one?

Review

timesofindia

8.0

Like a pizza, Manikandan's Kaaka Muttai is multi-layered; on the surface, it is all warm and inviting — a feel-good film about two kids and their simple desire and the earnestness in the filmmaking invites comparision with Iranian films like Children of Heaven. Then, there is a hard base to it as well and from time to time, the film turns into a commentary on the class divide in our society and how it is exploited by wily politicians, an allegory of the effects of globalization, and even a satire on media's obsession with sensationalism, a la Peepli Live.

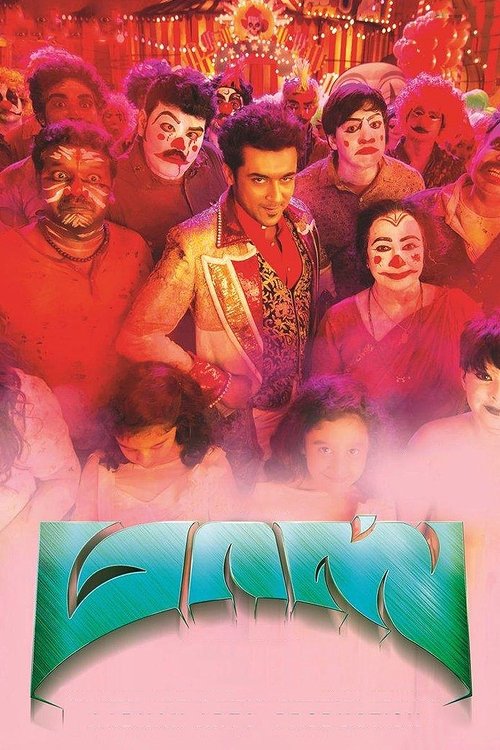

The story begins with a plot of land which acts as a playground to the kids in the slum being sold off to make way for a pizza outlet. The pizza place is opened by a film star (Simbu in a cameo) and the enticing visuals of the pizza create a burning desire in these two boys (the terrific debutants Ramesh and Vignesh) who cannot even afford the normal egg and resort to drinking crow's egg (hence their nicknames — Chinna Kaaka Muttai and Periya Kaaka Muttai) to buy and eat a pizza. The lads' father is in prison, their mother (young Aishwarya Rajesh boldly taking on the role of a mother of two) is running the show at home with great difficulty and their grandmother is almost an invalid.

But on hearing their wish, an empathetic railway lineman called Pazharasam ( Joe Malloori), lets them take (read steal) the coal from the yard, and they start hoarding the money they earn by selling it. But after being driven out by the security at the pizza outlet because they are "kuppathu pasanga" and dressed in rags, there begins another round of chasing after money — this time, to buy new clothes. They manage that as well but at the pizza shop, the manager slaps one of them and tells them to buzz off. This incident, however, is captured on a mobile phone and soon, it turns into a media-fuelled, raging controversy. The small-time thief and his cohort (RJ Ramesh and Yogi Babu portraying characters who come across as a modern-day take on some of the characters played by Goundamani and Senthil) in the locality decides to use the video to blackmail the owner ( Babu Antony), the local MLA decides to get some political mileage out of it, the media grows a conscience and starts talking about class divide, and the shop's owner strikes a deal with the cops to hush up the issue, while the boys, who fear their mother might come to know of their embarrassment, go missing. The film does seem a little less sure when the boys are offscreen, but Manikandan manages to tie up all these strands with an ending that is not only satisfactory but also heartwarming.

Manikandan seems to have the knack to make even the most mundane interesting and it is evident right at the very start of the film when the two boys playfully take turns to read out the statutory warning against smoking and drinking. Much of the humour in the film comes from sharp observations. For example, the ration shop can provide two television sets but when it comes to rice, "adutha vaaram dhaan varum"; when the boys diss the homemade 'pizza' that their grandma has made for them saying, "Pizza-la nool noola varum aaya", she retorts, "Kettu pona dhaan nool noola varum"; a woman asks her neighbour to come for a protest because they will get biriyani and money; a friend of the pizza shop owner who keeps making inopportune remarks. The gags are also on their mark — the politician giving bytes dressed in lungi, the boys nonchalantly walking past a TV reporter without realizing that she is talking about them, a drunken man being taken to his home on a toy car, a TV anchor cutting off a panellist every time he tries to make his point and moving on to a break or worse, showing the video again...

The director also doesn't shy away from showing us some of the darker aspects of poverty — one of the kids in the slums cunningly steals mobile phones from the footboard passengers of passing trains; the thief and his cohort steal the manholes from apartments and sell them to make money; even the cable connection in the boys' home is acquired illegally. And, the two lads themselves reach a point where their ravenous need to somehow taste a pizza (one of them even tells their mom, "Pizza dhaan venum... Appa venaam" when she talks about how she doesn't have the money to get him out on bail) forces them to think of taking up crime to get the money required. There is also squalour and abject poverty (though, the camera and the scenes never linger long for us to feel squeamish; this is, after all, meant to be a feel-good film, as evident from the jaunty score) — the boys' one-room home with a curtain separating the living room and the toilet, the Cooum serving as their pool, the lack of money to arrange the funeral of a departed one... A different film might have used all these elements to give us a heavy-duty social drama that would have only ended up as the 836th time a 'socially-conscious filmmaker' holding a mirror to our society and hectoring us for our callousness.

Refreshingly, Manikandan refrains from doggedly going for our tear ducts in his portrayal of the lives of these underprivileged (though, there are a couple of deserving moments that brings us to tears); he also doesn't indulge in heavy-handed sermonising or needlessly attacking the haves (we even get a boy from a well-to-do family who is sort-of friends with the boys to the extent of saving a slice of pizza for them — though the older one refuses to take it deeming it a leftover) and instead presents things mostly in a matter-of-fact manner. Yes, there is difficulty and sorrow in their lives, but there is also an abundant amount of ingenuity, endless optimism, and indefatigable spirit and this is what makes these characters memorable and helps the film soar.

Read More

Rangan

10.0

> When PIZZA was replaced for the CROW'S EGG.

India is the world's largest film producer, but when it comes to the international standards, it falls short. They make movies for the domestic market only, just like the largest mango producer in the world and consumes it all with a 1% export rate. Even small countries that have no big market like India competes with the European standards. But in the recent times the changes have been seen, lots of parallel cinemas are made; is what called alternate to the masala films (mixed genres). The young generation supporting it, both from the audience and the filmmaker.

The sad thing is they're choosing a wrong movie to represent the country in the Oscars, so as a result ending up with a disappointment every time. I thought last year they failed to pick 'The Lunchbox' as similar to this one for this year. I don't know whether they would have won the trophy, but these films need to be recognised in a big stage like that. Making into the final five reveals all the India films are not random musical beats. So my point is India missed the bus to the venue Dolby Theatre Hollywood, LA, USA for the second consecutive time.

This film feels like a feather fallen out of the British film 'Slumdog Millionaire', but it was totally a different genre except sets in and about the slum kids. A simple story, yet very moving. Two young brothers go regularly to pick the crow's egg in an vacant site near their slum since they can't offer chicken eggs. When the place is bought by a largest pizza chain in the city to bring up their new branch, the kids fix their mind to taste their first pizza and put all the effort to make it happen. But again, they have to face all the odds and that's where the narration takes the turn before heading the end.

> "I want pizza too, not dad."

Without the prior experience the two kids were so awesome in their performances. They two won the best child actor award at the Indian Academy Awards, including the film as the best children's movie of the year. The debutant director really did a great job, especially knowing there's no mass market for newcomers. I think the producers, Dhanush and Vetrimaran to appreciate for this movie to happen. No doubt why it did better at foreign markets than the local. Especially Kollywood does good in the East and Southeast Asia, unlike Bollywood that dominates Europe and North America.

You know why this little film is a must see, because Indian films are known for different standards to the rest of the world, but when they make one out of their comfort that puts automatically a must watch. That's not the only reason, there are hundreds of themes yet to explore in Indian cinema and this is one of that. Like the two cute movie characters and their one innocent task, the scenes and music were well supported throughout.

Some of the domestic issues that India is suffering from long back like the social status brought into the light with this. There's no equal respect in society for all the communities, only it is judged by their lifestyle. Most of the third world's social backward is only for this reason and obviously the lack of basic education. So it is really good when a movie is not only identified for its entertainment, but the message it carried out. It is an adorable, smart, funny, emotional, enjoyable family movie and one of the best of 2015 other than the Hollywood's or English language films. In the world cinema fanatic circuit, Indian films is the least followed, but this one is not to be missed.

9.5/10

Read More