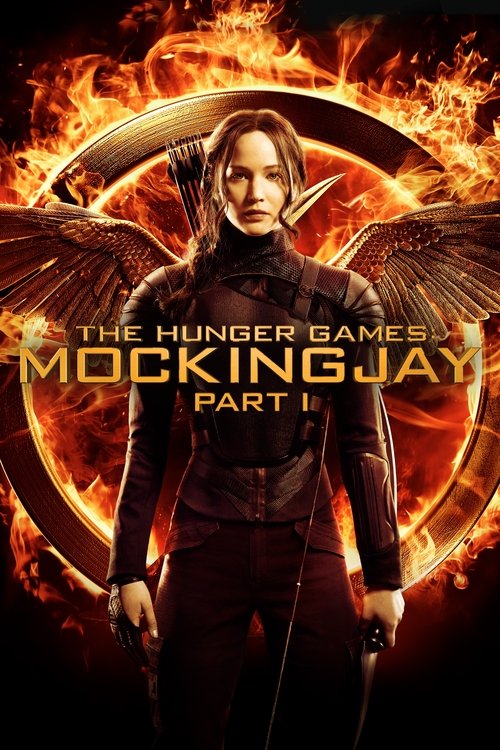

2012

The Hunger Games

Science Fiction, Adventure, Action, Thriller

8.0

User Score

23044 Votes

Status

Released

Language

en

Budget

$75.000.000

Production

Lionsgate, Color Force

Overview

In a dystopian society where the Capitol forces each district to send two young tributes to fight to the death in a televised spectacle, a girl volunteers to take her sister’s place, setting the stage for a struggle of survival and defiance.

Review

tmdb87069603

8.0

Very well made movie with quality writing, acting and cinematography.

**Pros**: strong performance from the star. Technically excellent.

**Cons**: Seems to me that the ending was premature but perhaps intentionally so - for a sequel? Character development is largely weak but there are a lot of characters and already a long movie so I suspect a lot was left on the cutting room floor.

Despite some weakness, still a compelling movie worth a watch if not up to all of the hype.

Read More ltcomdata

8.0

Stories about revolution can be quite good. But stories about why a revolution is needed are invariably great. The Hunger Games is such a story.

The movie (for the most part), closely follows the book, and does a good job of it. It also sets up the next book/movie beautifully, even better than the book itself does.

The premise, of course, is borrowed from Ancient Rome, when gladiators and/or criminals an/or people whom the emperor wanted killed were forced to fight each other to the death in a public arena for the entertainment of the general populace. And just as decadent as Rome was back then (only rescued from itself by the rise in prominence of The Christian sect), so the "Capitol" is now portrayed in the film/book---and the film portrayed the affluent decadence of the Capitol quite well.

In this particular instance the "tributes" were chosen at random from among children aged 12 through 18, and it was meant as retribution and reminder of the "crimes" the 12 colonies committed by reveling against the authority and rule of the Capitol 74 years ago. At the public "reaping", when a boy and a girl were chosen to become the sacrificial tributes at teach of the 12 colonies, the Decree of Punishment was read and the colonies were reminded that this punishment was established to demonstrate how weak the colonies were in comparison with the Capitol, in that the Capitol could take the most prized possessions of the colonies (namely, their children), and the colonists themselves could do nothing about it. And to really rub it in, the colonists themselves were forced to watch the tournament proceedings.

I have to say, the punishment is deviously clever from the point of view of the Capitol. It certainly keeps the Colonies divided in spirit (they were already segregated physically, with no communication between them allowed by the Capitol), for in cheering for their own children they are therefore cheering for the defeat---and therefore death---of the other colonies' children. It also keeps colonists divided within each colony, for there can only be one champion, which means that in wishing their children not to be chosen at the reaping, each colonist is thereby wishing that someone else's children be chosen. Furthermore, in celebrating that their children were not chosen, they are also, incidentally, celebrating that some other person's children will likely die. And for the families of the chosen children, in supporting their own family member during the tournament, they are incidentally supporting the death of the other family's child. And it keeps the population of the colonies low, which the Capitol would want to promote (less chance for another insurrection if the population is low): for the youngest are taken, before they are married, and those who survive the yearly reapings will think twice about having children of their own and having them go through this traumatic process year after year during their most vulnerable adolescent years. And furthermore, the Capitol encourages the colonists' tacit endorsement by rewarding the winner's Colony with extra food that year (hence "The 'Hunger' Games"). But it is all manipulation, in the end.

In fact, by the end of the Games, right before being killed himself, one of the most avid killers among the children realizes just how much it all is the Capitol's manipulation, how pointless it all is to those who participate, and how, in the end, he didn't really have a chance---that he was destined to die from the beginning---and that killing or being killed is all that not only the Capitol, but also his Colony, want from him. An eye-opening realization for someone who up to this point had been quite eager to kill his fellow children.

Given the vicious circumstances which were thrust upon these children---none of which is their fault---the question naturally arises: how should a child bound under the moral law behave? Should he try to win, by killing the other children? Should they try to win at all? Should they let themselves be killed, in order that another might live?

Of course, the obvious moral choice would be for none of the children to participate in this horrendous form of reality television: if they do not fight each other the show is not interesting, and eventually it is discontinued. The children would likely still be executed, along with many of their own family members in reprisal from the Capitol. If one thinks in terms of consequences only (utilitarianism), then this would be the wrong approach: after all, they would say "it is better that one person survives than that they---and all their families---die". But such thinking is quite repugnant, however logical it is. Consequentialism is missing a big piece of the moral landscape, namely that we ought not to become evil ourselves in our fight against evil. Yes, the consequences of "civil disobedience" as could morally be practiced in this scenario are more dire in terms of the quantity of damage made. But they are much more preferable in terms of the quality of damage made. By fully participating in the carnage (and inflicting some yourself) you become complicit in the very evil which oppresses you. Similarly, your family, and even your colonies (and all colonies, for that matter) become part of the system, and in some tacit way endorse it---for they all want their children to live, and tacitly support the other colonists' children's death. Furthermore, what kind of person does one become after killing 23 children by brutal means at a very young age (when the impressions of life still shape us in a powerful manner)? What kind of society does one help create when one has inwardly become a psychotic monster? What kind of society abides criminal monsters in its midst?

But, some will claim, it is unrealistic to expect each and every child to be morally minded, especially when some children (from two different colonies which are highly favored by the Capitol) actually volunteered for the "honor" to represent their colonies at the tournament. What is the correct moral response when civil disobedience is not an option (no opportunity) and some, if not most of the other children are out to kill you, whether by pleasure or need to survive?

It seems to me there are two possible moral responses. one of them is the route of self-defense, whereby one does not intentionally kill or go out of one's way to engage the enemy, but tries to flee as a first alternative, BUT where one DOES defend oneself against the attacks of others, and inflicts only as much harm as is necessary to stop the aggressor, AND only if absolutely necessary one uses lethal force. In the end, very likely, the Capitol would force matters to a resolution, either by forcing "aggressors" and "defensors" into a particular area (very good television), or by artificially creating natural/artificial disasters which killed whomever they disliked most. But, again, this would be the Capitol's doing: an evil force acting evilly which one cannot stop. One would have been preserved from sinking to doing/becoming evil.

The other moral route, the more perfect route, would be the route of Jesus: to willfully become the sacrificial lamb for the sake of spiritual (and therefore) moral change. The martyrs of the Church have for ages followed this route, to the spiritual benefit of the whole Church, and the cultural benefit of all humanity. The spiritual benefit is quite and readily seen through the Communion of Saints, whereby these martyr's love renews and creates the Church anew, greatly adding to the spiritual gifts of which the rest of us partake---gifts which slowly transform us for the better, over years and generations. And it is this transformation which over the centuries affects culture. Gradually better people live their lives out in gradually better communities. And Love wins out at the end of time. After all, very few societies nowadays would consider it acceptable to inflict the tortures which were inflicted to prisoners (especially Christians) in the ancient days of Rome: we are all repulsed by the Capitol's Decree of Punishment. If we only partook more of those graces which Christ offers through His Church!

One particular odd feature of the book (and the film) is the avoidance of any mention of God or religion whatsoever. Not even empty phrases deriving from religion appear ("My Gosh", "God willing", Christmas, Thanksgiving, etc.). Why is that, especially when the subject matter so clearly lends itself to a religious treatment? Why is that, when the least historically educated among us would have heard the stories of the Christians ushered into the Colosseum to be executed/sacrificed? The closest religious reference is when Katniss Everdeen improvises a type of tribute around a fallen friend and ally in the game by creating a bed of flowers for her: the very earliest expressions of the religious impulse, as some Anthropologists would tell us. Why has the author scrubbed her book from religion at all? Is she so antagonistic to religion that she will not abide it in her book, even when it seems quite apt? If so, the bed of flowers tell us that the most primitive of religious impulses remain with her still. Or is the author trying to appeal to everyone, thus removing religion from the surface of her story so as to not alienate people of different religion than the one she chose to portray, while at the same time infusing her work with religious themes at the substrate level, where they are more powerful? Or is her point that the despotic Capitol destroyed all hope quite successfully, even the Hope of God? Given the richness of the religious themes I see in this book/movie below the surface, I am very much inclined to believe that the last of these options is the correct one. But I may be seeing what I want to see, simply because I like the story.

Now, turning to the more artistic features of the movie: The most impressive performance was done by the actor who played President Snow. His facial expressions were insuperable and spoke tons in the few lines he delivered throughout the film. His performance was astoundingly good, his face delivering contempt, skepticism, and hatred (sometimes all at once) along with the "weight of office" while speaking seemingly innocuous lines, or even while congratulating the winners (there were two winners from District 12, thanks to the cleverness of Katniss Everdeen in turning the television show against its organizers!) of the 74th Hunger Games. He single-handedly set up the next movie installment.

But the casting of Peeta is all wrong. From the book it is clear that Peeta is not handsome at all, that Peeta is the boring guy who never had a chance when it came to women, and who doesn't have a chance when it comes to Katniss Everdeen who clearly has feelings for another guy. Which makes it all the more poignant that he is desperately in love with her, and is willing to give up his life for her. In the movie he is played by a movie-star-handsome actor who clearly would have trouble keeping women away from him, and who would therefore be quite self-centered and clueless, rather than the thoughtful man he is in the book.

Read More